When Nikos Kazantzakis was a young boy he would have watched his father and his father’s friends fight in the Cretan rebellions against the Ottoman Turks, who then ruled Crete. As a teenager and a young adult, after Crete became all a sovereign state, nominally under the Ottomans but ruled by the brother of the Greek king, he would have heard the stories told by these old revolutionaries. Kazantzakis’s father was a Καπετάν (“Kapetan”) or a leader of a group of guerillas. Nikos and his family, headed by his father Mihalis, lived in what was then known to the Greeks as Megalo Castro, but is now known as Heraklion or Irakleio. When the rebellions occurred families would have gone up into the hills to the old family village, or even deeper into the wilderness and waited there until the fighting was over – or for the fighting to come to them. In young Kazantzakis’s case the family fled to the island of Naxos and the port of Piraeus, next to Athens. The elder Kanantzakis, a merchant in ordinary life, would have been out with his fighters leading them into opportunistic attacks upon soldiers and officials of the hated Ottomans. The younger Kazantzakis would have grown up amidst periods of tense peace broken by frequent outbreaks of violence, repeated on a large scale over and over until finally, in 1898, freedom was secured.

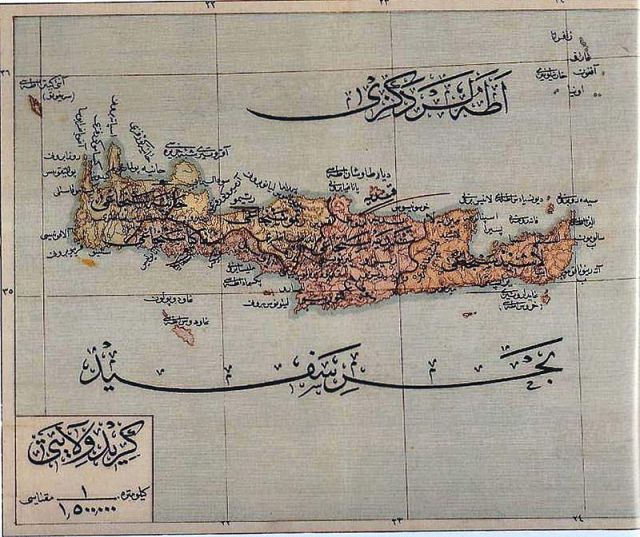

When Crete was Turkish.

The Orthodox Greeks of Crete rebelled during the 1821-1830 Greek War of Independence. At that time perhaps as much as 45% of the population were followers of Islam, many of them immigrant Arabs and Turks, as well as other ethnicities within the Ottoman Empire. However, a large proportion of them were also converts from Greek Orthodoxy, perhaps out of genuine conviction, but many would have done so in order to escape the tax on non-Muslims and to receive the benefits of being of the same faith as the rulers. The converts continued speaking Greek and were still related to the Greek Orthodox, but the links across the religions was often overwhelmed by the antagonism created by colonialism. In that war of 1821-1830 it is thought that some 21% of the Orthodox population died, whereas, driven into plague-infested cities, as much as 60% of the Muslim population died. The Ottoman rulers executed a number of bishops from the island, just as they hanged the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, reasoning that they had failed in their jobs of keeping their people in line.

Cretan Insurgents, 1898

Although the southern part of mainland Greece and some of the islands achieved independence after the intervention of the UK and France, Crete remained under the Ottomans. The Orthodox Cretans rebelled again in 1841 and 1858. The Great Rebellion began in 1866 and lasted until 1869. It ended, as usual, with a major effort at “pacification” combined with some concessions. Among the concessions was an agreement that the Greeks of Crete could have some limited self-government. There were smaller revolts in 1878 and 1889, both unsuccessful, and after which the Turks reneged on self-government. In 1895-1896 there was a final rebellion. As it continued into 1897 Britain, France, Italy, Russia, and Austro-Hungary concluded that the Turks needed to be forced to allow the Greek Cretans to rule themselves. Thus they sent their navies and armies to Crete to occupy the major towns. While there a Moslem mob attacked foreigners and troops in Megalo Castro, and they killed the British Consul. The Ottoman armed forces were obliged to leave the island, and as noted above, the Great Powers imposed sovereignty on the island by inviting Prince George of Greece to come over and be the High Commissioner of the Cretan State. In 1913 Crete formally became part of the Kingdom of Greece.

A Parade of British Troops in Candia (i.e. Megalo Castro, or Heraklion) in 1907-1908, when foreign troops remained in Crete to ensure Cretan self-rule and to keep the Ottoman Turks out.

This was the local history that Nikos Kazantzakis grew up with. As a young man he went to Athens to study to be a lawyer, although I do not think he ever practiced as one. He then went to the Sorbonne in France and did a dissertation on Nietzsche. He returned to Greece and spent much of his time translating Greek and French works – mostly philosophy – into Greek. However, he was beginning to think that his real calling was to write, and that in Demotic Greek. After a few short works he spent fourteen years writing a sequel to The Odyssey in over 33,000 lines, more than twice as long as the original. Published in 1938, it was not well received, perhaps suggesting that no one should try to outdo Homer. He was caught in Athens by World War II, and during the war he began the book Zorba the Greek, which was published in 1946 (English 1952). The immediate success of this led to a flurry of books, including novels about the Greek Civil War in Macedonia in the 1820s (The Fratricides, 1949/1954), the Catastrophe of 1921-23 in Anatolia (Christ Recrucified, 1948/1954), a fictional biography of St. Francis of Assisi (God’s Pauper, 1953), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1942; 1950-1951, 1955). Kazantzakis died in 1957, and is buried in the walls of Heraklion. His home has been recreated in a museum in Heraklion.

Hollywood made this Irish-Mexican actor, Anthony Quinn, the epitome of Greek manhood. You see his image everywhere on Crete, although even his character was not Cretan.

Zorba the Greek was adapted and made into an English-language film by the Greek Cypriot film-maker Michael Cacoyannis in 1964. The film did very well, earning three times its cost and meriting seven Oscar nominations, winning for Best Supporting Actress, Best Cinematography, and Best Art Direction. It was with this movie that Kazantzakis became well known to the English speaking world. In 1988 Martin Scorsese adapted The Last Temptation of Christ into a controversial movie; you’ve never seen John the Baptist and Pontius Pilate portrayed correctly until you’ve seen them done by Harry Dean Stanton and David Bowie, respectively!

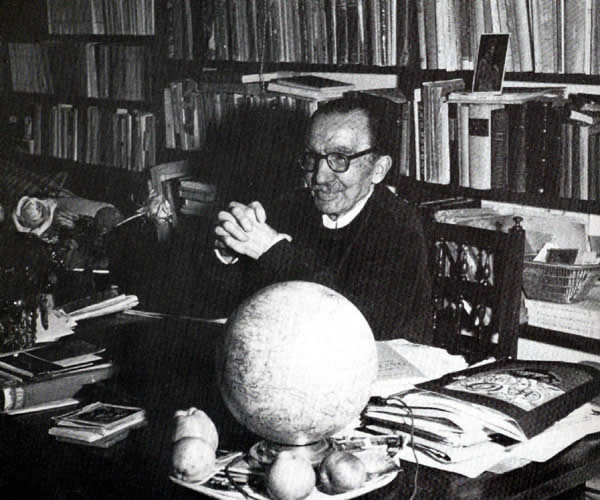

Kazantzakis in 1956 in his study in Antibes, France

A novel that has received less attention is Captain Michalis (written 1949-1950, published 1953), or as it is known in North America, Freedom or Death. It tells the story of the leaders of a guerrilla band in the unsuccessful rebellion of 1889. Set mostly in Megalo Castro and the hill villages around it, it tells the story from multiple perspectives, including that of Nuri Bey, the Muslim blood brother of Captain Michalis, and Pasha Effendi, the governor of Crete. Chapter 5 is a meandering through Megalo Castro with several dozen characters engaging in conversation, prayer, meals and other ordinary activities, as if in the calm before the storm. Perhaps influenced by James’s Ulysses, it shows how the Muslims and Christians overlapped, and how the tension was sometimes undone by good will. The main character, the Captain himself, is undoubtedly brave, but also monstrous in his unfeeling relations to his family, his need to drink alcohol, his intense desire for honour, and his inability to feel remorse for killing and murdering, even when the victim was accidental. I think that Kazantzakis wanted to deconstruct what “heroism” was, an ideal he would have received from his father and still lives in Crete and other parts of Greece – this combination of honour and horror. There is a strong theme of Cretan “machismo” throughout the book that would make it unpalatable to 21st century tastes, but I do not think Kazantzakis presents it uncritically – rather he shows it in all its brutal ugliness. Women’s voices are heard as well, in the Captain’s wife and daughter, in the mistress of Nuri Bey, and the women of the villages; however, it was a deeply patriarchal culture, and the women are overwhelmed by the needs of the patriarchs. There is also an aspect of folk tales and magical realism, as Stamatis Philippides noted in an article from 1997.

I am told by one of my neighbours that the book is hard to read, because large parts of it are in Cretan dialect (he grew up in Macedonia). I of course had to read it in an English translation (in a copy I bought in Russell’s, in Victoria, BC, Canada), but I look forward to having enough Greek that I can at least read a part of it. The translation I read, by A. N. Doolaard, had some obvious errors in it – the local clergy, for example, are referred to as “Pope”, which is a bit bizarre; the word should have been transliterated as “Pa-pass” or just translated as “Father”or “priest”. Some academic reviews also noted misunderstandings of the original Greek. Nevertheless, Kazantzakis’s genius shines through, despite any infelicities of the translator. It’s a good if challenging read. Despite some misreadings by some it is not an exaltation of Cretan heroism but a narrative analysis of it – its power, and its failings. In the end the Captain dies pointlessly. The reader knows from the other side of 1898 that this is the penultimate rebellion, but one of the least remembered among many. Michalis dies as much for his own honour as for the freedom of Crete, and to join with those who died violent deaths in the decades before. His type became unnecessary in Crete after 1898, and Kazantzakis seems to say, “We shall not see his like again. Amen.”