I did the above graphic over twenty years ago, back in the day when I used WordPerfect on my Apple computer. I think it holds up pretty well, and so I have uploaded it for general consumption here on the blog.

A few comments to explain things.

- The Book of Psalms was written in Biblical Hebrew. Some of the psalms show evidence of being older than most (Psalm 68 exhibits some archaic features of the language, mainly rare words), and others display evidence of being later than others (Psalm 119).

- The critical text that is used for translations from the original Hebrew is that of the Biblica Hebraica Stuttgardensia (“BHS”), which is based on the Leningrad Codex, a manuscript of the entire Hebrew Bible (also known as the Tanach or Old Testament) made in Cairo in 1090 CE. The critical text also draws on other Masoretic texts and the Dead Sea Scrolls and compares it with the Greek translation of the Second Century BCE known as the Septuagint, and other ancient translations.

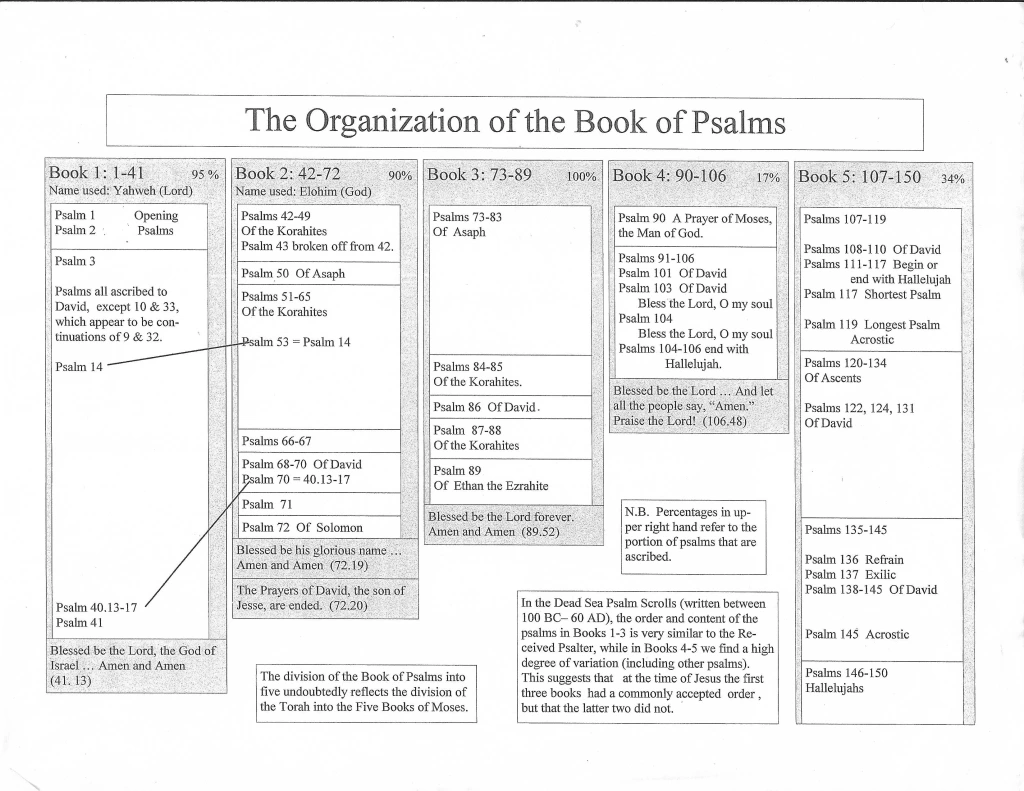

- The Book of Psalms is a collection of collections. While the psalms were written individually, at some point editors began putting them together in groups. These groups appear to include “The Psalms of David” which ends at Psalm 72.10, the psalms of Asaph (73-83), and the Songs of Ascent (120-134). These groups or collections were then put together in larger groups. The evidence for this is the replication (with slight variations) of a couple of psalms – Psalm 14 shows up as Psalm 53, and part of Psalm 40 reappears as Psalm 70. This suggests that later editors, even if they saw the repetition, were loathe to challenge the integrity of the earlier collections.

- At some point, perhaps building upon earlier arrangements of collections, an editor organised the psalms into five books. This undoubtedly is an echo of the Five Books of the Torah, and is a correspondingly late construct. This organization underlines the use of the psalms as Torah, or instruction, prophecy, and law. Each of the books, except the last, has a doxology at the end that begins, “Blessed be . . .” The books are not all the same length – an indication of their relative lengths is suggested by the hight of the columns in the graphic.

- We do not know exactly how the psalms were sung, or the original context for their singing – we have neither the tunes nor their place of use. Any suggestion otherwise is just speculation, although there is evidence to suggest that many were originally used in the worship of the Jerusalem Temple.

- That said, it does appear that the psalms used refrains, and that there was a call and response between a cantor and a choir, or perhaps two choirs.

- The psalms in the original Hebrew do not have metre as such, as we associate with hymns and songs, but rather, they emphasise parallelism, where a thought is expressed and then re-expressed in different words or in a new way in the second half of a verse. This is sometimes expanded upon a third time.

- At least some of the psalms appear to have been accompanied by lyres, psalteries, trumpets. ram’s horns, tambourines, and other percussion instruments.

- Biblical Hebrew distinguishes between prose and poetry by the verb forms used. Whereas in prose Hebrew will use the waw/vav consecutive in narrating past events, this is absent in poetry. While it is still usually pretty clear what is untended, this occasionally introduces a degree of ambiguity that the author might be deliberately playing with.

- An important issue is that originally the psalms would have be sung, and so the primary experience for Israelites would have been of “hearing” the psalms, not reading them, as we do. The person singing the psalm may have worked off of a text, but there may have been the freedom for the cantor or choir to engage in “composition in performance.” This term was devised by Milman Perry and Albert Lord to describe how illiterate Serbian poets created long epic sung poems, and that ancient Greek epics such as the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed the same way. Thus, the psalms originated in a culture that was primarily oral. Thus, the later writing down of the psalms and their collection and editing suggests a shift in how the psalms were experienced, and the increase in the authority of a set text over that of the cantor. The use of the Book of Psalms as a source of Torah and prophecy is the end result of this process.

- Many of the psalms have ascriptions in the Masoretic text, sometimes as simple as “Of David” but sometimes suggesting the tune, or explaining the context of the psalm with reference to an historical incident elsewhere in the Bible. In the first three books of the Psalms over 90% have such ascriptions, but the latter two books have far fewer. Most scholars believe theascritions were added as part of the editorial process.

- A couple of the psalms appear to have been divided in their transmission, namely psalms 9 and 10, and psalms 42 and 43. Neither 10 or 43 have ascriptions, and they carry on the style and thought of the previous psalm.

- Psalm 1 and 2 do not have ascriptions – Stanley Walters, my Old Testament as Scripture professor, suggested that these function as an introduction to the Book of Psalms.

- In Book One the name of God is consistently “Yahweh” (the personal name of God, Yahweh, almost always replaced with LORD in English translations), whereas in Book Two it is consistently “Elohim” (usually simply translated “God”). It has been suggested that an editor may have gone through the collections to make sure the address to God was the same throughout. Other scholars have suggested that some psalms may have originally been addressed to Baal or other Canaanite gods, and that they were adapted for Israelite use by replacing the name of the God.

- Among the Dead Sea Scrolls the most common biblical texts were the psalms. Owing to the fragmentary nature of the psalm scrolls recovered from the caves in the Judean desert it is not clear whether these were scrolls that were the actual Book of Psalms, or selections from the psalms made for liturgical use or study. The order of the psalms in the scrolls usually follows that found in the Masoretic text, especially in Books One through Three, but in the latter two books the order varies significantly, and psalms that are not in the canonical text are included. This instability of the text towards the end suggests that the Book of Psalms was, at the time the Dead Sea Scrolls were hand-written, still a work in progress. Psalms might have been added, and others removed, and the actual text might have changed.

- The academic books that I use the most in reading the psalms are: William L. Holladay, The Psalms through Three Thousand Years: Prayerbook of a Cloud of Witnesses (Minneapolis MN: Augsburg Fortress Press, 1993) and Peter W. Flint, The Dead Sea Psalm Scrolls & the Book of Psalms (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1997).