A Sermon preached on The Second Sunday of Lent, 1 March 2026 at The Anglican Church of St Thomas the Apostle, Kefalas, Crete, Greece. The readings were Genesis 12:1-4a, Psalm 121, Romans 4:1-5, 13-17, & John 3:1-17.

This morning, as advertised, I want to talk a little bit about faith, especially as used in the Letters of Paul. In Romans 4:16 we heard that “For this reason the promise [to Abraham] depends on faith.” Now what is the nature of this faith?

In 1983 an American New Testament doctoral student named Richard Hays at Emory University, Atlanta, had his PhD dissertation published. It was entitled The Faith of Christ: The Narrative Substructure of Galatians 3:1-4:11 (my version is the 2nd Edition, Grand Rapids MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2002). This was the equivalent of a bomb being set off among Pauline scholars, as the issue was what Paul meant by πίστις Χριστού. Those of you who know some Greek know that πίστις is the word we normally translate as “faith” and Χριστού is the Greek genitive of Χρίστος, which we transliterate as “Christ”, and corresponds to the Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ, (māšīaḥ), meaning the anointed one, such as a king or Zadokite priest.

A genitive means that it is a most often a possesive, although it varies across languages. Thus, one must distinguish between a genitive grammatical form and the grammatical function. In English a genitive is marked by the addition of “‘s” to a noun or name, eg. This is Frances’s dog. In Standard Modern Greek, that’s Αυτός είναι ο σκύλος της Φράνσις. The real question is how we are to understand the relation of these two words πίστις and Χριστού – its function. Traditionally, Χριστού has been understood as an “objective genitive” which is to say that it is faith IN Christ. We are the subjects, and we have faith in the “object” of Christ. Hays in his 1983 dissertation made a strong argument, based on narrative logic, that in fact πίστις Χριστού should be understood primarily, in Galatians 3:1-4:11, at least, as a “subjective genitive” – that is, that it is the faith OF Jesus – his faithfulness, his obedience, his trustworthiness. Thus, to say that we are saved by πίστις Χριστού means not that we are saved by our faith in Jesus, but that Jesus’s faithfulness saves us.

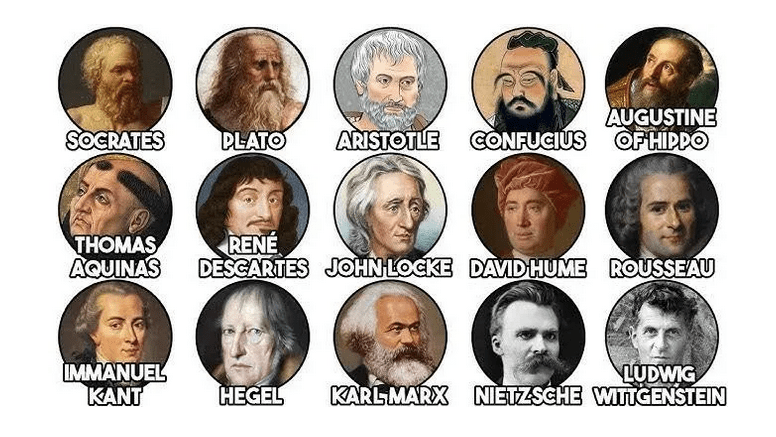

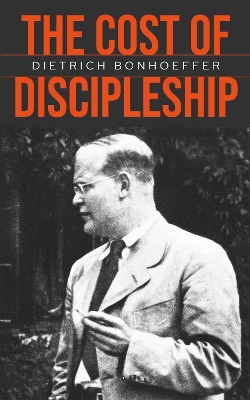

You might be able to imagine why this was so controversial. Back in 1517 Martin Luther nailed his ninety-five theses to the church door in Wittenberg, Germany, thereby inadvertently but very unapologetically setting off the Reformation and the transformation of Europe. Central to his message was the idea that we are saved not by doing good works, like buying indulgences and helping to pay for that new basilica of St Peter’s in Rome, but by faith in Jesus. Luther saw that faith leaping out of Paul’s Letters, especially Romans and Galatians. Right conduct was important, but it followed from that faith, and ultimately it was God’s grace given through Jesus Christ that saved a person for eternal life.

Evangelical Christianity felt it was incredibly important that people have this faith – not some weak connection to church, or a mere membership in the denomination by virtue of baptism, but a lively faith that could express itself. Yes, a person with faith did also sin from time to time, but hoped and trusted that, with frequent repentance and confession one would still stand in the grace of God.

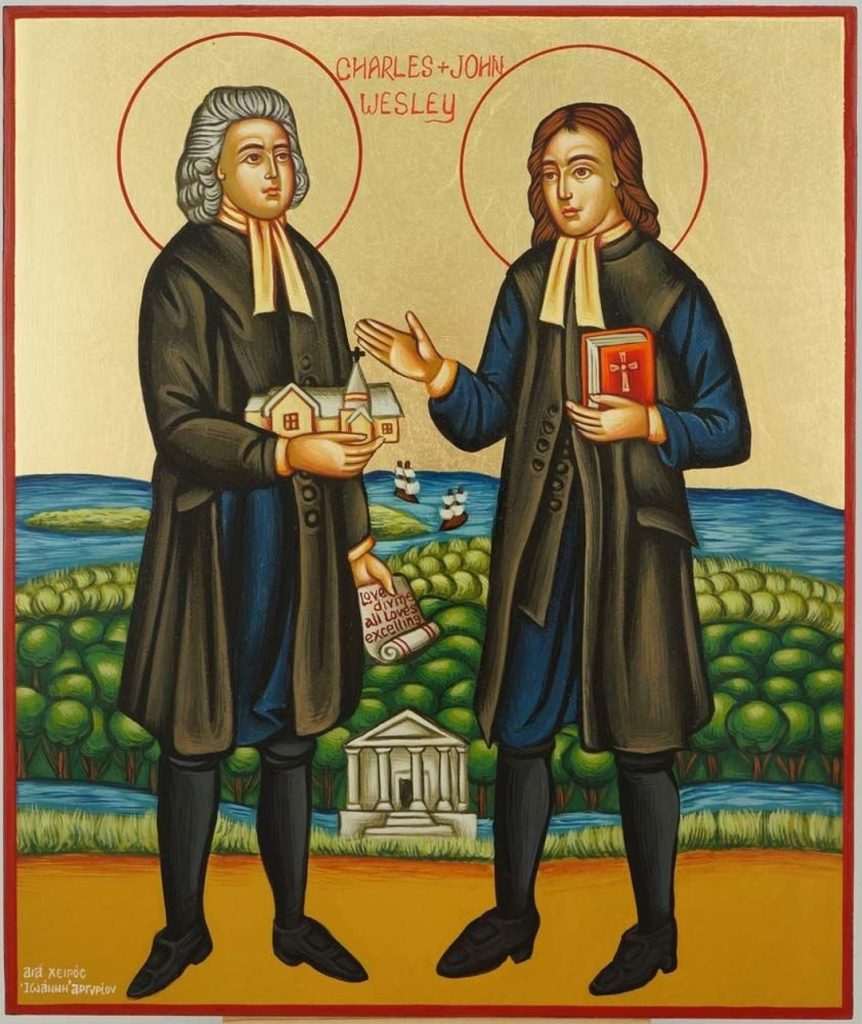

In the English speaking world evangelicalism might be said to be started in the 18th century by the brothers John and Charles Wesley, two Church of England clergy. Each experienced a dramatic warming of the heart – a conversion or a renewal of faith. Later called “Methodists” because of there methodical way of studying scripture and praying in groups, they laid great emphasis on a person’s individual commitment to Christ, and the emotional and affective knowledge of this. This “enthusiasm” for faith alarmed many church leaders, and they were made unwelcome in many Church of England parishes. The brothers began to preach in the fields to hundreds and thousands, and wrote hundreds of hymns for their followers. While some of this form of evangelicalism stayed within the low church parts of the Church of England, after their deaths the “Methodists” organised themselves into a new Protestant denomination.

For some, the emphasis upon belief meant that the sacrament of baptism needed to be reserved for those who could profess belief in Jesus Christ. Thus, Baptists broke away from the churches that baptised infants and young children, and required a testimony by a candidate for baptism before being initiated.

All of this is very much in contrast to a High Church Anglican, Roman Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox understanding, which is that by baptism and the eucharist one is incorporated into the Body of Christ. In this thinking some of us may be saints, some great sinners, and most of us are in-between, but all are saved by the grace of God because of God’s actions in Christ Jesus. Thus, what Jesus did in his teaching, death, and resurrection, is far more important than the content or quality of faith of any single believer. We are all works in progress, in this way of thinking.

Well, the controversy rages on, as much as you can call scholarly articles going back and forth raging. I have here a recent contribution coming from Nijay Gupta, an American who got his PhD at Durham, Paul and the Language of Faith (Grand Rapids MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2020). Gupta notes a variety of ways to translate πίστις that go beyond the two alternatives considered by Hays.

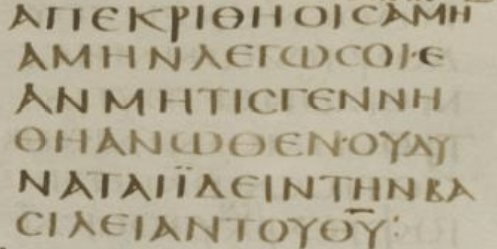

Let me pause here and make a connection with the gospel reading. Chapter 3, verse 3: Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω σοι, ἐὰν μή τις γεννηθῇ ἄνωθεν, οὐ δύναται ἰδεῖν τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ. Amen, Amen, I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God without being born from . . . – how does that phrase end? Most people would say “born again”. However, our translation says, “born from above”, with a footnote admitting the alternative translation. People argue about the best way to translate that Greek word ἄνωθεν – “again” or “from above” – but my friend and colleague Andrew McGowan who teaches at Yale University suggests that the ambiguity in the Greek should be kept. It is both.

Maybe that ambiguity is there also in Paul. When Paul uses the phrase πίστις Χριστού perhaps he means both the faith or a kind of trust in Jesus, and at the same time mean the faith of Christ, the faithfulness of Jesus and his obedience even unto death, even death on a cross. This is a faith that dwells in us by the power of the Holy Spirit. In the end it is all the grace of God. I experience the faith of Christ in me as my faith in Christ, and a kind of unearned faith of God in me, despite all the evidence of my fragility and sinful nature. Perhaps Evangelicals, Catholics, and Orthodox all have part of the truth of the matter.

The good news is that whether subjective or objective, we have faith. This faith is not something that is static, but is dynamic and growing, faith seeking understanding (as St Augustine would put it). This morning I have suggested that it is both ours and put in us by God. May we continue to grow in the faith of Christ, into the full stature of Christ. May we grow as a church, in numbers, in spirit, in our impact on the community around us. May the faith of Christ that is in us justify us and make us righteous.