This Advent, in the Year of the Great Pandemic 2020, it seems appropriate to look at The Apocalypse – that is, The Revelation of John. This is the eighth of twenty-six short reflections.

Remember Genesis? Not the book, the band. They started off as teenagers in the late ‘sixties doing the usual Beatles covers. Peter Gabriel was the lead singer, and played flute, and his schoolmates Michael Rutherford and Tony Banks played bass and keyboards, respectively. After their first album Steve Hackett joined on guitars, replacing one of their school chums who felt he really did not know how to play well enough. They went through a number of drummers and finally got the jazz trained Phil Collins. This was the classic lineup of the early ‘seventies that, along with Yes and King Crimson, defined Prog Rock back when it was cool.

One of the songs that they did for over a decade was 1972’s Supper’s Ready, which took up a whole album side of Foxtrot, their fourth studio album. As is typical with Prog Rock lyrics, it is a bit opaque, but according to one source it was based on the nightmare Peter Gabriel’s wife had while sleeping in a purple room. The Wikipedia article quotes Gabriel saying that it is “a personal journey which ends up walking through scenes from Revelation the Bible… I’ll leave it at that.” Somewhere I read that it was related to a group of people taking a lot of drugs and one person having a bit of a bad trip.

It’s a lot of pretty bizarre imagery, very little of it actually from Revelation, but the last section goes like this (from a concert in 1976, when Gabriel had left the band and Collins had taken over the singing – remember when Phil Collins had hair? I think Bill Bruford is playing drums, but I’m not sure):

There’s an angel standing in the sun,

and he’s crying with a loud voice

“This is the supper of the mighty one”

Lord of Lords, King of Kings

has returned to lead his children home

to take them to the new Jerusalem

The New Jerusalem is a powerful image, so powerful that a bunch of otherwise apparently agnostic Prog Rockers used it for one of their greatest songs. It has been used by others, of course:

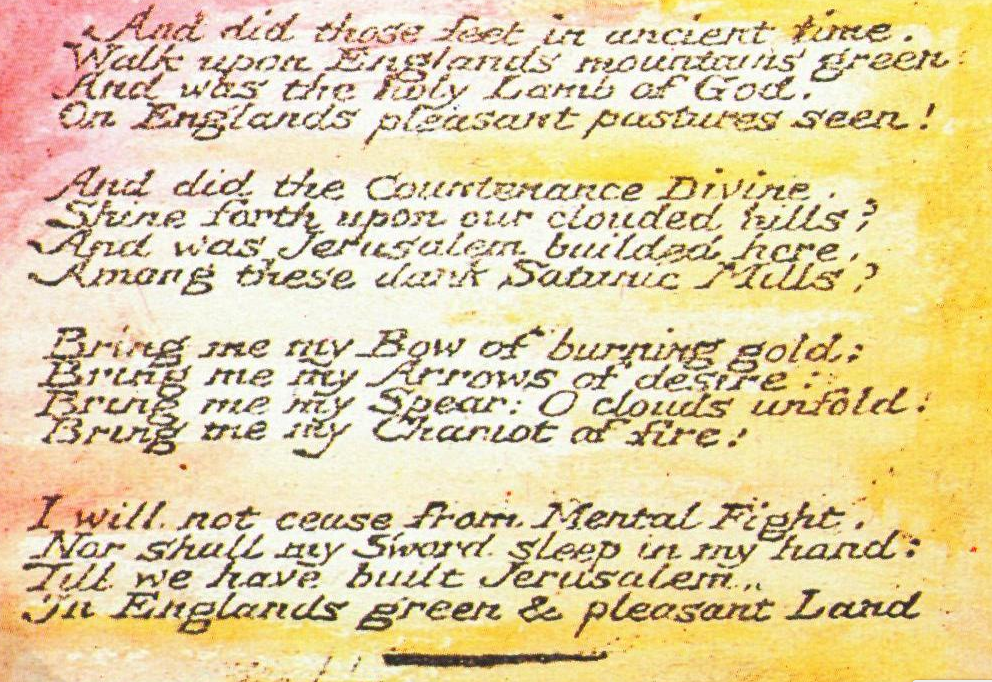

This is William Blake’s poem “And Did Those Feet In Ancient Times” published by that strange poet and printer in 1808 in his book Milton. It was pretty much unknown until Hubert Parry set it to music in 1916; it’s the hymn setting used above in the 2011 wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton. Many of us remember that its theme and music played a major part of the Danny Boyle’s opening ceremonies of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. As well, it inspired the title of the Academy Award winning “Chariots of Fire.” Over the past century it has become sufficiently popular that some consider it to be the national anthem of England.

Here is what it looked like when Blake engraved and printed it in the preface of “Milton”:

The poem is inspired by the myth that Jesus came to Glastonbury as a young man, as an employee of Joseph of Arimathea, who supposedly was a tin merchant; it was first described in the 13th century. When my colleagues and I would sing it occasionally in the Diocese of Niagara we would always insert am emphatic “No” after the second line.

Of course, Blake probably knew this. His interest was less in the myth than in the establishment of a better England – one less of satanic mills and one more like what is described in Revelation 21 (see below). Blake was inspired by the French Revolution, and while not a fan of the Terror or war, he still wished some of the egalitarian impulses had reached England. So he dedicates himself to the challenge of building Jerusalem in England. This meant that the hymn became an anthem for other Christian socialists as well – regularly sung in Canada at meetings of the CCF and NDP.

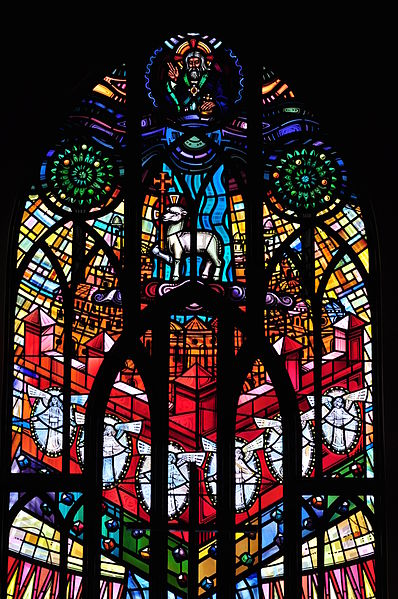

John the Divine describes his vision thus:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. 2 And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

“See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

4 he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

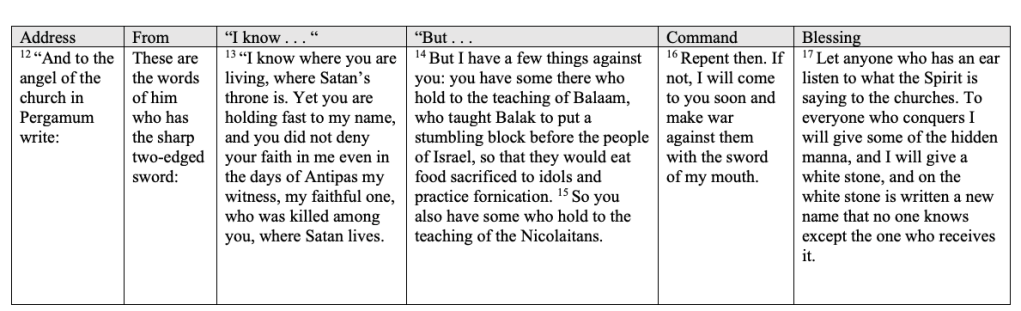

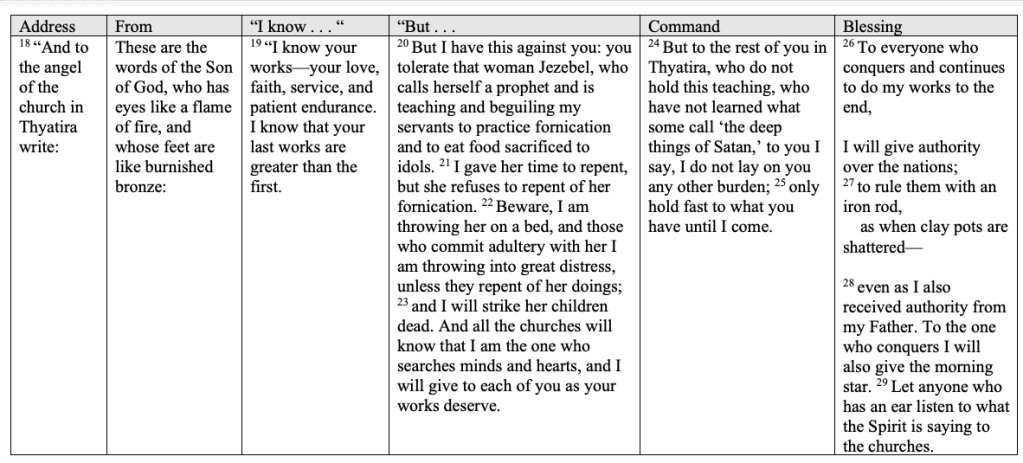

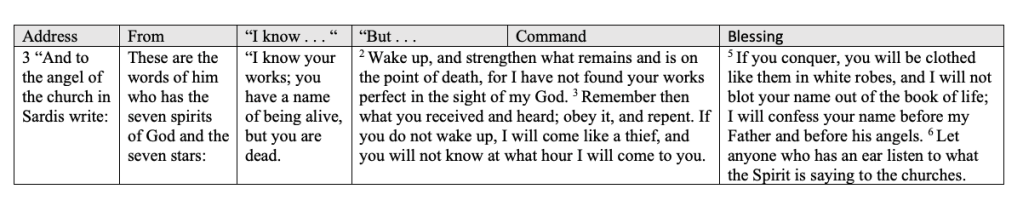

for the first things have passed away.”5 And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making all things new.” Also he said, “Write this, for these words are trustworthy and true.” 6 Then he said to me, “It is done! I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end. To the thirsty I will give water as a gift from the spring of the water of life. 7 Those who conquer will inherit these things, and I will be their God and they will be my children.

This image is not original with John the Divine, though. It comes from Ezekiel, who wrote in the middle of the Babylonian exile, roughly five centuries earlier than John. He describes it at great length in chapters 40-48:

In the twenty-fifth year of our exile, at the beginning of the year, on the tenth day of the month, in the fourteenth year after the city was struck down, on that very day, the hand of the Lord was upon me, and he brought me there. 2 He brought me, in visions of God, to the land of Israel, and set me down upon a very high mountain, on which was a structure like a city to the south. 3 When he brought me there, a man was there, whose appearance shone like bronze, with a linen cord and a measuring reed in his hand; and he was standing in the gateway. Ezekiel 40.1-3

That same angel shows up in Revelation 21:

15 The angel who talked to me had a measuring rod of gold to measure the city and its gates and walls. 16 The city lies foursquare, its length the same as its width; and he measured the city with his rod, fifteen hundred miles; its length and width and height are equal.

The main difference between Ezekiel and John is that John’s New Jerusalem is much, much larger – a vast home for God’s people who have suffered so much.

Second Isaiah, writing at the end of the Babylonian Exile, picks up on the image of the New Jerusalem, and describes the city as bejewelled in Isaiah 54:

“11 “Afflicted city, lashed by storms and not comforted,

I will rebuild you with stones of turquoise,

your foundations with lapis lazuli.

12 I will make your battlements of rubies,

your gates of sparkling jewels,

and all your walls of precious stones.

13 All your children will be taught by the Lord,

and great will be their peace.

14 In righteousness you will be established:

Tyranny will be far from you;

you will have nothing to fear.

Terror will be far removed;

it will not come near you.

I do not take this passage literally. This is largely an extended metaphor for a transformation that is beyond words. Why do I say that? Because in Revelation 21.1 it says, “and the sea was no more.” Why would the sea disappear? Does this make sense literally? What does God have against the sea?

However, if we read it symbolically we see the sea as a symbol. For a landlubber like John, the sea was terrifying and chaotic. When he writes that “the sea was no more” he means that there is no more terrifying chaos. There is order and redemption. In the new creation, however we understand that, mourning, death, pain, and crying is no more.

The New Jerusalem, like the new heavens and the new earth, is something inaugurated by the death and resurrection of Jesus. It already is, was, and will be. What Christ is in his resurrected glory we will become. In the meantime, we work to create a piece of that New Jerusalem, a foretaste of that [lace with the heavenly banquet, here in our green and pleasant land, whether that be England, Canada, or Greece. So let us work out our salvation in fear and trembling, following the one who “has returned to lead his children home to take them to the new Jerusalem.”

Tomorrow I will talk a bit about time in Revelation.