Introduction

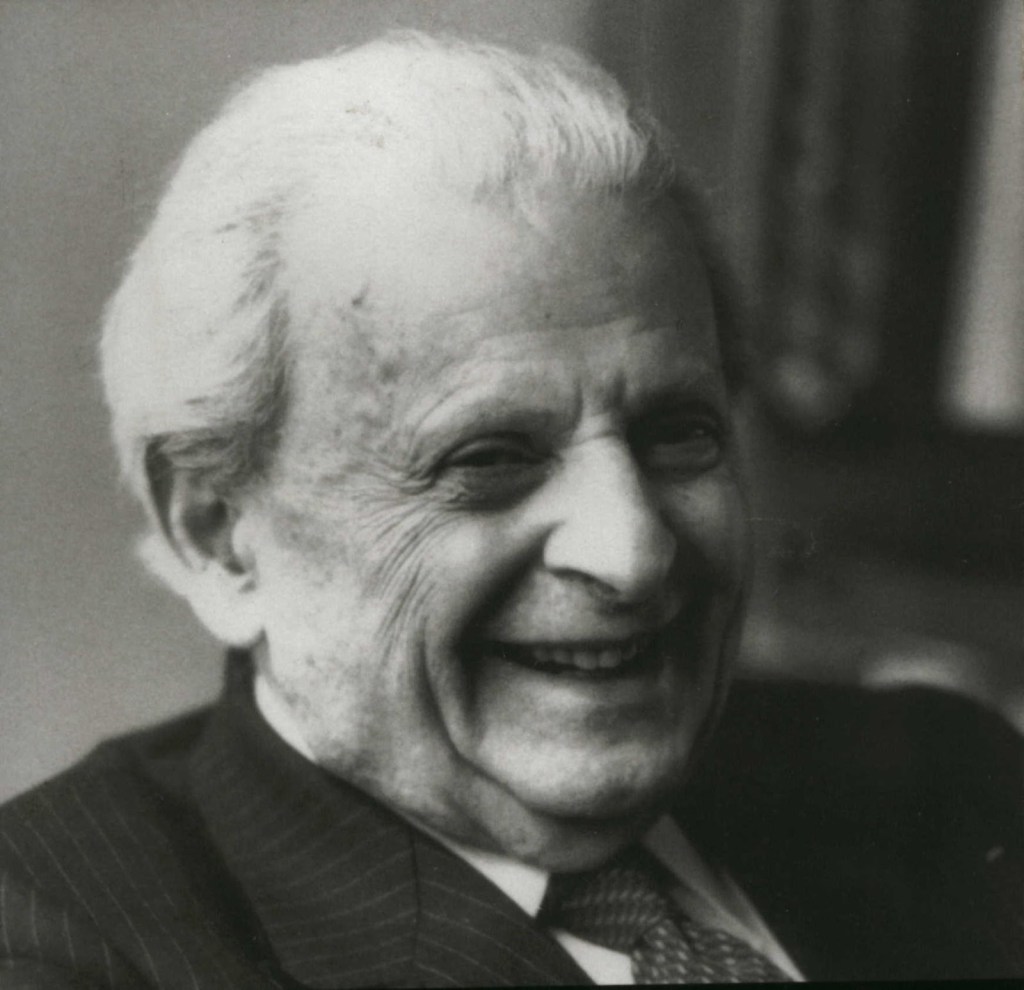

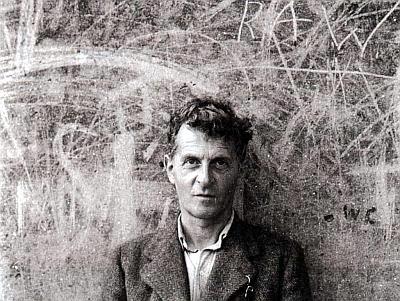

I want to talk a bit about how I find that the philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) and Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995) seem to say similar things about the nature of human language. The relevance to theology is that humans are required to use language, but often make claims in God-talk that need qualification. This will also lead us to consider some of the theme of deconstruction as described by Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), and how that relates to theology, the interpretation of scripture, and the activity of following Jesus the Messiah.

I think I need to do this in four parts. The first part talks generally about what philosophy is for those who have never bothered to read much about it, and I frame it as a personal account. The second part is biographies of Wittgenstein and Levinas, pointing out some similarities in the lives that may have contributed to their fashioning of philosophy. The third part is a discussion of their respective philosophies of language, noting the similarities. The last part draws out the implications for anybody of faith.

People who already know philosophy or are acquainted with Wittgenstein and Levinas may jump forward to the third part (when I have written it!).

A Career in Philosophy

In the autumn of 1981 I was a student on academic probation at the University of Toronto. I had arrived the year before with the intention of becoming a physicist, perhaps winning a Nobel Prize. I had arrived with two scholarships and had graduated at the top of my (admittedly small) high school. I thought I was hot stuff. However, between alcohol and an inability to adapt to the discipline of academic work in a university, I managed to fail not one but two courses. I thought of dropping out, but my father (who had had similar problems when he was at university) encouraged me to go back. Fortunately, the University of Toronto, a large, impersonal institution, had fairly generous terms for failing students, and kept me.

One course that I had passed was a half course led by Professor Willard Oxtoby in Religion and Law. I do not think I did particularly well in it, but while doing the readings and a minimal amount of research for the essays I came across hints at the discipline of philosophy, which looked at all manner of things, but especially the meaning of life, and the place of religion and how philosophy may serve it or take it down. My brother Bill Scott had studied PPE at Oxford – Philosophy, Politics, and Economics – and from him I had gotten a whiff of what the field involved. In Religion and Law I heard references to Plato’s Cave, and Aristotle’s categories, as well as names like Kant and Hegel. So, for better or for worse, I started over, in the second year of a four year degree, changing my major to philosophy.

The University of Toronto then and now is possibly the best place in Canada to do a BA in philosophy, if only because it is so large that almost every branch of the academic field is taught there. Arguably McGill University in Montreal has some better known philosophers (Charles Taylor being the preeminent one), but I did not know that. At the age of nineteen I was remarkably ignorant.

Over the next three years I read through the history of philosophy:

- The Greek Pre-Socratics – Thales, Anaximander, Heraclitus, Parmenides, and a few others. This was interesting because most of these authors are known to us only in quotations and fragments. They spanned the sixth to fourth centuries before the common era (“BCE”).

- Plato – Some of this was really about Socrates, about whom Plato wrote, and who was usually the leading character in his dialogues, but after an early period Plato used his master’s voice to put forth his own ideas, particularly those about “forms” or “ideas” – the belief that the material world was less perfect than the world of numbers or ideals of justice, love, and truth, and that our mundane existence only replicates these as shadows.

- Aristotle – I read his ethics and metaphysics, and to a lesser extent his categories.

- Plotinus – I did a half-course in Neoplatonic thought, which was thought to influence early Christian theology.

- I also did a course in the thought of Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, which introduced me to the two critical Christian thinkers from the Latin west of the 4th-5th century and 13th century, respectively.

- My training then jumped to the early modern philosophers – Francis Bacon, who described an early form of the scientific method, and René Descartes. Then followed the Empiricists David Hume John Locke, and the Rationalists Baruch Spinoza and Wilhelm Leibnitz.

- Immanuel Kant – mainly his metaphysics in The Critique of Pure Knowledge, which attempted to resolve the differences between the Rationalists and the Empiricists. I also read a bit of his ethics, but not enough.

- G. W. F. Hegel – who reacted to the abstract, ahistorical analysis of reason of Kant by describing the world-spirit of Geist unfolding throughout history in the dialectic of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. Mostly I just read his Phenomenology of Spirit.

- Karl Marx – the Soviet Union was still very much with us, and I had not yet heard of the reforms taking place in China, so it made sense to read some of the writings of Marx and Engels. As Marx claimed to be a materialist interpreter of Hegel, it also made sense to see what he made of the older German. I did not come away with any desire to be a Marxist.

- My reading then jumped up into the 20th century, with a couple of courses in symbolic logic.

- I also took a course in Wittgenstein’s philosophy, as found in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) and Philosophical Investigations (1953). As far as the mainstream of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Toronto was concerned, Wittgenstein was the culmination of the history of philosophy, and one could not be a modern academic philosopher in the 1980s without taking him into account.

- I also did some courses on epistemology, aesthetics, and the philosophy of religion (which overlapped with the sociology of religion).

- Finally, I did a course on Buddhist Philosophy, and I focused on the writings of Nagarjuna (c. 150-250 CE).

Now, anyone who knows anything about philosophy will notice a lot of gaps. For one, apart from that last course on Buddhist Philosophy, this was all very much Western Philosophy. There was a dim sense that there were other philosophies, perhaps from China or Japan or India, but these were never raised and seemed to have no impact on whatever it was that I was studying. So much for Islamic Philosophy, Chinese philosophies, Jewish Philosophy, much less Indigenous ways of knowing.

As well, apart from the Neo-platonists, I missed out on any of the Post-Aristotelians – the Stoics, the Epicureans, and Medieval philosophy was viewed just as various types of theology. I missed out on Thomas More’s Utopia and Bishop Berkeley’s radical idealism in Principles of Human Knowledge. I missed out on a whole bunch of 19th century Germans: Fichte, Schelling, Schleiermacher, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche; some might suggest that I wasn’t missing much there, but I did notice this gap. I did not read Bertrand Russel or any of the other Anglo-American Analytical philosophers, or the Logical Positivists, except when they were commenting on Wittgenstein.

Another huge gap was what was described as Continental Philosophy – Henri Bergson, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. It may well have been taught in corners of the Roman Catholic college of St Michael’s, but I never came across it nor was encouraged to go read it. Continental philosophy was the kind of thinking that I was directed to and told, “Whatever they are doing, don’t do that.”

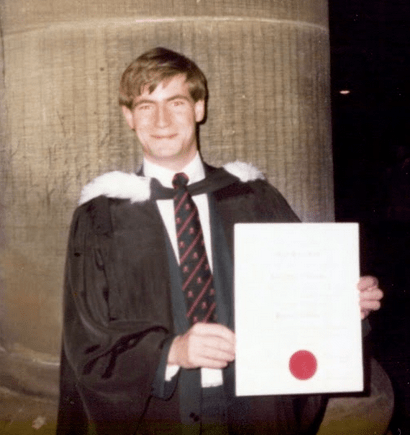

The result of this at the end of my four year degree is that I did graduate in 1984 with some familiarity with many of the “greats” of western philosophy, but none of it went particularly deep. While I might have been accepted into a Master’s program in philosophy, no one was telling me to do so, and I was more interested at that time in preparing for ordained ministry. My training in philosophy set me up well for the three-year divinity degree, especially in theology, but I thought I was more or less done. In addition to philosophy, I also took some courses in religion, studying Islam and Hinduism.

I earned a Master of Divinity in 1988, was ordained, and set off into parish ministry, dealing with Sunday liturgies and youth groups, baptisms, weddings, and funerals, as well as social action and administration. In 2002-2003 I took a year’s sabbatical and did another master’s degree, a Master of Theology at Harvard University’s Divinity School, where I encountered Feminist Theology, Black Theology, and the “dangerous” continental philosophy. On my own I began to read this man I had never heard of before, Emmanuel Levinas. In order to understand him, I had to read his major teachers – Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Thus I taught myself Continental Phliosophy. The nice thing about having by then done three degrees is that I could study on my own. More about Levinas in the next post, as well as my more recent re-placing of Wittgenstein in the history of philosophy.