I’ve just spent two-and-a half days in Toledo, Spain, which was, for the last thirty-seven years of his life, was the home of Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known to people then and now who cannot wrap their tongues around Greek names as “El Greco” – “the Greek”. An ambitious man, he was born and raised on the island of Crete outside of what was then called Candia and is now known as Irakleio. He learned to paint there, but in Greek Orthodox Crete that meant “writing” icons. Two of those icons are at the Benaki Museum in Athens, and neither are in good condition, nor show any sign of greatness.

Crete at the time had been under the control of the Venetian Republic for several centuries, and he would have been exposed to western, Catholic styles. Wanting to learn from the best, he went to the big city, which for him meant Venice, where he learned to paint in the “Mannerist” style. While he appears to have had modest success there, he wanted greater things, and so went to Rome. He did not achieve the success there he desired, but he did make the acquaintance of a Spanish cardinal, and so made his way to the cultural centre of Spain, the Imperial City of Toledo.

There are dozens of his works in Toledo, many of them forming retables or reredoses behind altars built in churches and monasteries of the late 16th century and early 17th. His work stands out from those by other painters that went before and after. The ones before were not particularly realistic, and the ones afterwards tended to be quite realistic; the vast majoity are not very interesting. The paintings of Theotokoupolis are striking and impressive for two, perhaps three reasons. First, the personages in it often appear elongated, long and thin, especially if they are the central character. It is suggested that this makes them appear more holy, although there is also the effect that as one’s eyes scan these painted bodies one’s perception is that the body is floating and ascending. Second, his colors are bold, especially the greens, the reds, and the blues. More subtly, the reddish-brown background that is used as a foundation on the canvas is not always overpainted, but allowed to show through, thus creating a sense of depth. Third, in his large paintings (not his portraits of apostles or commissions of living figures), they are heavily populated; this can be seen in the Burial of Count Orgaz and the Disrobing of Christ (above).

The paintings of Theotokopoulos are like figure skating. Just as the elite skaters at the top of the field are excellent technicians and makes it look easy, so it is easy to think that his paintings are simple. It is only when you look at the works of his students or others of his time that you realise how good he is. There is a freshness to his paintings that inspired the Impressionists. His paintings, while firmly in the expected genres of his time, still look out of place. There is a weird, uncanny quality. When I see his work I constantly think, “How did he get away with that?”

Part of this may go back to his experience as an icon painter. Icons, notoriously to western viewers, do not have perspective. Theotokopoulos can do perspective, but he is not wedded to it. His painting of Toledo is not what Toledo actually looked like, but the painting captures somehow exactly what I remember it looking like. He is more interested in the spiritual meaning of what he is painting than being rigidly tied to renaissance ideals of perspective. Thus, he warps perspective to bring things into play, highlighted here, diminished there. Furthermore, his faces are paradoxically both non-realistic and very realistic. At first glance they look almost generic, quickly painted portraits. However, I found that the longer I gazed at them the more real they seemed, and conveyed something of the character the Cretan was trying to portray.

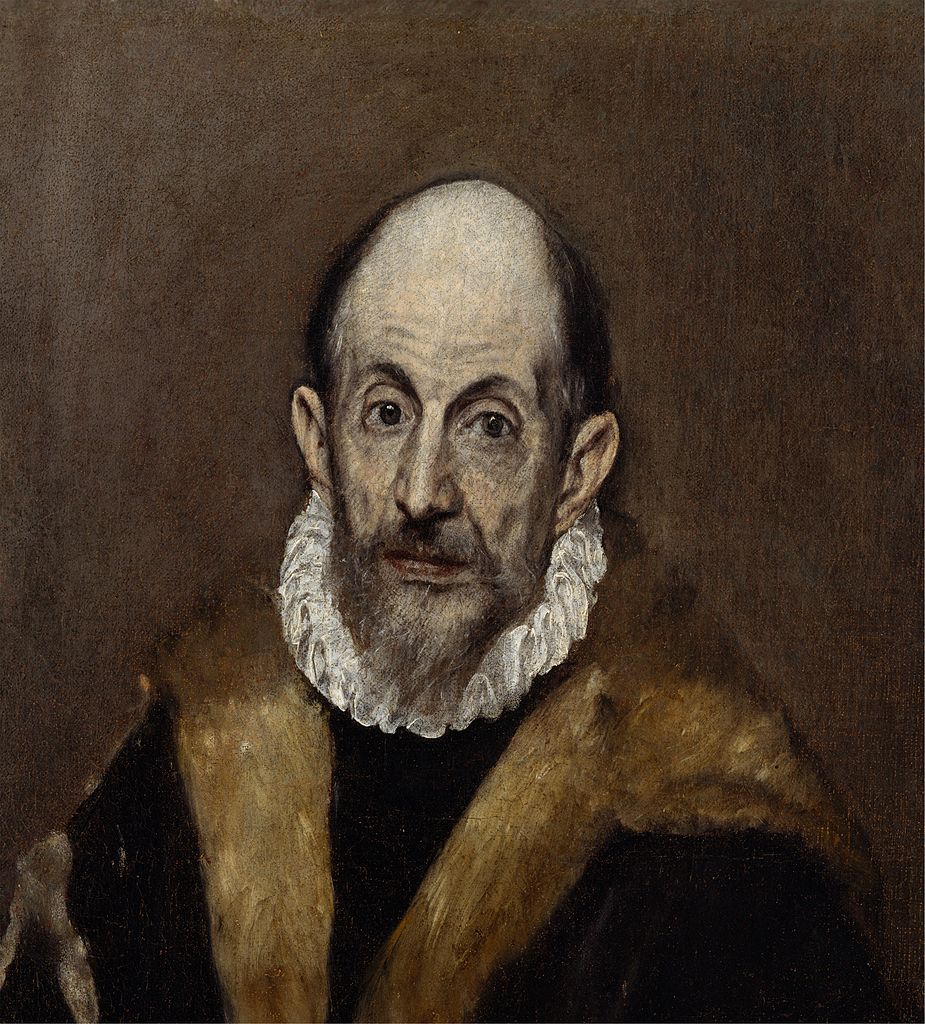

The same is true of his portraits. The picture at left, often identified as a self-portrait, captures the assymetry of a true face, and the clear-eyed repose of someone who knows a thing or two. There’s no flattery, and it is neither a mere sketch or a hyper-realistic portrait. It catches a moment in the man’s life,no more and no less.

Theotokopoulos is unique and left no school to follow him, but he inspired the Impressionists in the 19th century and after a couple of centuries of neglect he received great attention from the beginnings of the 20th century. He used to be characterised as a mystic, but art historians over the past one hundred years, looking at the documentary evidence of his contracts, his lawsuits about fees, and his marginalia in contemporary books on art, find him to be an artist of strong opinions about technique and his own worth, and not given to ethereal musings. Since the last quarter of the 20th century he has become the centre of a small tourist industry in Toledo and the great museums of the world, where ordinary people briefly look at his paintings, and art historians write vast tomes that discuss everything about hos context and the history of the painting, but don’t explain why it is important. My own view is that we see in his work someone who had a particular vision and figured out how to express it in canvas and paint, uprooting himself several times to do so, and thriving despite his striking style. I am glad that he was celebrated in his day and has left us so much to continue to inspire us.